“Art must be dangerous.” At first glance, the statement sounds provocative. But in today’s art ecosystem, oversaturated with trends, surface-level aesthetics, and instant validations, it speaks to a deeper yearning for meaning. Art must risk something. And Helen Ifeagwu, the Nigerian-Austrian artist and journalist, embraces that challenge with striking clarity.

Raised between cultures and trained in journalism, art, and marketing across three top European institutions, Helen has always lived in the in-between. Between cultures. Between disciplines. Between memory and futurism. Her work doesn’t merely depict; it interrogates. Her realist and Afrofuturist paintings ask what it means to belong when you’re split between borders. They ask what the future of Black identity looks like when technology, nature, and tradition collide.

Her art is tender yet fierce. Dreamlike, yet grounded, and rendered in a surreal realism that transports viewers into alternate dimensions of possibility. In this exclusive interview, Helen speaks with raw honesty about the personal pain and beauty behind her work. She reflects on identity politics, dual heritage, and the responsibility of the Black artist today. Art, she insists, must do more than adorn white walls. It must unsettle. It must provoke. It must reframe the entire conversation.

FAB: Your work carries a lot of emotion. When you are creating, do you lead with the feeling itself, or does the emotion reveal itself only after the work is done?

Helen Ifeagwu: I think it’s always a bit of both. For me, emotion and experiences are where ideas come from. At first, I might start with an emotion, usually something that makes me feel. I’m often inspired by other pieces of art, like music (I love music), literature, movies, or anything that gives me a spark of inspiration. It’s usually rooted in emotion anyway. Then I might think, Okay, I want to make art around this, or How can I interpret this visually? I’m usually very calculated with my work; it’s never too abstract or random. I tend to plan ahead. And I guess that planning also stems from emotion, something I’m trying to express or convey.

The colours I use, the symbols I choose, and the fact that I use a lot of symbolism – those all come from emotion too. Then sometimes, as I’m working, I might realize midway through the process. Actually, this has sparked a new idea, or now I feel like adding something else. It’s like building blocks. You start with one thing, and then you keep adding. And of course, when I finish a piece or even during it, I might reflect and think, Actually, I don’t like this, or, This now makes me feel something different. That shift is part of the creative process too.

Silence, Symbols, and the Power of Detail

FAB: In one of your previous interviews, you mentioned that a lot of your work is inspired by memories. What memories do you find yourself returning to over and over? Are there any you’ve resisted working with?

Helen Ifeagwu: I think I don’t rely on memory as much anymore. Now it’s like I’m trying to capture something from the future, if that makes sense. A lot of my work is quite spiritual, and I’m trying to create a kind of window into a different dimension or a different pathway of thought, visually. And that could be a memory someone might have from the future in the past or of the past in the future. It probably doesn’t make much sense. But I think the way I engage with memory is more futuristic.

Maybe there’s some nostalgia in my work, but these days, I’m very forward-focused and future-focused. And maybe memory shows up in the sense of symbolism. For example, a symbol I use often is sculpture: stone sculpture, marble, and the female body as seen in classical sculptures. That’s kind of nostalgic, because it refers to the idea of the first humans and the first pieces of art and relics that were created to celebrate humans. So that’s a really important recurring symbol in my work. That could be considered a memory and could be something nostalgic.

FAB: What role does silence play in your practice? You say you also like music in general, but metaphorically or literally, have you had to learn to block it out or…?

Helen Ifeagwu: Silence, I think, plays a big role in my work. I believe silence and boredom often go hand in hand, and that’s where ideas are born. When I work, it’s usually just me; I’m in my studio for hours by myself. I often listen to things, but sometimes I don’t.

There are moments when there’s no music playing, I’m not listening to anything, and I’m just thinking about ideas. I might be looking at a piece and thinking, Okay, I could change this or that. I love silence because it creates a good space for new ideas. It’s like a vacuum of energy; you can fill it with whatever you want. Silence is very important to me, especially when I’m conceptualizing an idea. I think the hardest part isn’t even getting the idea—ideas are everywhere. Having ideas is fine; writing them down is easy. But translating an idea into something visual that makes sense—that’s the challenge.

I actually have a notebook full of ideas, like 50 or more. I jot down sentences, fragments, and things I want to paint in a series. The ideas come quickly, and I try to capture them immediately. But then I get to the canvas and realize it’s one thing to have an idea, but it’s another to bring it to life visually. That part is tough. And for that, I need a lot of silence, a lot of thinking, sitting, and sometimes even meditating.

I always imagine that every idea starts with something being seen, an observation that opens a new dimension, a space where that idea can live and evolve into something tangible.

Helen Ifeagwu

FAB: Do you feel that your work has developed its own internal language or vocabulary? What are some of its ‘keywords’—visual or emotional?

Helen Ifeagwu: Yes, for sure. I think that often, when I finish something, and I believe every artist feels this way. It kind of becomes its own entity, its own energy. It’s like, Okay, I made this; it came from me, but now it’s for others. It’s something for people to interact with and interpret. When I have exhibitions or people view my work and tell me what they think, I often notice recurring themes in their interpretations. Like you said, the idea of the work having its own narrative.

I always include some sort of observer in my pieces. You’ll usually find an eye in my paintings—lots of faces, symbols representing women, men, humans, nature, technology, metal, and chrome. I believe the observer is probably the most important element. The observer creates the reality in which the piece can be set. I always imagine that every idea starts with something being seen, an observation that opens a new dimension, a space where that idea can live and evolve into something tangible.

Resistance vs. Healing: How Art Holds Space for Both

FAB: Art can be both an act of resistance and a form of healing. How do those two energies interact in your own work?

Helen Ifeagwu: Healing is maybe the easier one to answer, because with every form of art, or every time you create art, you’re healing a part of yourself. Creating art is being true to one of the most natural parts of being human: being a creator. When you physically make something, it makes you feel a certain way because you’re deeply in touch with your true essence of being a human. We’re meant to create things, I believe. We’re often distracted in this world by jobs and responsibilities, but I really think we’re all meant to create in some form. So it’s very healing for me. If I can paint for 12 hours straight, I feel so happy. It heals something in my soul. It’s deeply nourishing.

I think every artist has to battle some form of resistance. People often look at you and your work and wonder, What are they doing? Is this sustainable? Why would they choose this path? You’re constantly met with resistance. You have to be really strong and truly believe in yourself and not care what others say. And that, in itself, is an act of resistance. Because so many of us are influenced by those around us, it’s natural. But if you have your own vision and stick to it, that is your form of resistance.

FAB: When does your art stop belonging solely to you and become something for others? Is that transition ever difficult?

Helen Ifeagwu: Ah, all the time. I think about this a lot. It also depends on how and what medium you work in. With painting, you can collaborate with others, of course, but many painters, myself included, tend to work alone. We finish the piece, then exhibit it and start talking about it. Through that process of interpretation, writing, and cultural exchange, that’s when it becomes something for society. But initially, it’s yours.

If you’re making music, a play, or a film, those are often collaborative from the start. But for me, it’s when I show my work and talk to people about it—that’s when it becomes something for everyone. It becomes part of the community, in a sense. It’s not mine anymore. Also, when you’re filming your process or sharing on social media, where people can interact in real time, it already starts to feel like a group effort even while the idea is still being formed. That changes the experience too.

FAB: Has there ever been a piece that was hard for you to let go of?

Helen Ifeagwu: Yes, definitely. In the beginning, actually, most of them. When I first taught myself how to paint, there was this period where I was shocked that I could even make something. At first, of course, I hated everything I created. But then I started to improve and think, Wow, I made that. I would finish something, and someone would ask to buy it, and I’d say, No, I want to keep it in my house. It felt like my baby. I had worked on it for so long. The idea of giving it away was tough. But now, my mindset around painting has changed. It’s much more abundant. I believe I can make something, love it, give it away, and make something new the next day. And that’s okay.

I believe silence and boredom often go hand in hand, and that’s where ideas are born.

Helen Ifeagwu

FAB: What’s a material or medium you’ve used that surprised you and how it behaved or transformed your message?

Helen Ifeagwu: I am very simple; I stick to oil paint. I wouldn’t say any of them changed my message per se, but perhaps opened up a new world of possibilities for me as an artist. For example, when I challenged myself to use textile paint and gouache… because I also do some gouache illustrations for other things, like wedding stationery. I realized that every medium is its own thing; each has its own set of rules and behaves differently.

Obviously, I’m an oil painter. If I use acrylics, it’s different, and it’s tough. You think you can do one type of painting, and then you try something else, and it’s a whole different playing field, you know? That’s why I actually stick to oil; it’s just my favourite and the easiest for me. But I think maybe gouache or textile paint would be the most challenging.

FAB: For some artists, creating isn’t just about expression. It’s about reclaiming space. What part of your story have you taken back through your work?

Helen Ifeagwu: I think perfectionism. I’ve always struggled with being a perfectionist. I am a perfectionist when it comes to details. Growing up, I was always told, You’re too focused on small things, especially in painting class or school art sessions.

I truly feel that if I didn’t have painting, I don’t know how I would have survived. Art has set me free in so many ways because I used to struggle a lot with my body image while growing up. There was a lot of perfectionism that turned inwards, in a destructive way. Now, I can channel all of that energy into my canvas; maybe the result isn’t “perfect”, but I can add layers and layers of detail.

I love putting detail into my work because it helps me focus that perfectionist energy. I always feel the need to adjust, improve, and refine, but now I do that in a productive way, instead of destroying myself or doing something harmful. Art gives me that outlet.

FAB: What’s something about your creative practice that no one ever sees, but that shapes everything you make?

Helen Ifeagwu: Oh, many parts. I think especially the early stages. I post on my social media, of course, like my process and stuff. But there are certain parts of the process that are so personal, and also, I wouldn’t film them because they can be kind of boring—like just researching a lot, falling into rabbit holes, making inspo boards, listening to music or podcasts, writing things down, and taking random notes here and there. Just very personal work that eventually becomes the seed for a painting. And then, finally, it becomes the painting itself.

FAB: Are there any specific podcasts?

Helen Ifeagwu: Many, many, many! I love one called “Know Thyself”. I’m always listening to that one. It’s really, really good. Very spiritual, focused on self-growth and development. They talk about all sorts of theories and aspects of life and reality. I’m always looking for spiritual information, to be honest. Always seeking. And then that usually sparks something, maybe an idea, a symbol. And then I’m like, Oh, this could be a painting. If you don’t mind, maybe I can find an example? Just random sentences I jot down, like, This is an idea. This is another idea.

FAB: Do you ever feel that beauty, especially in art, can mask pain? And how do you balance aesthetics with honesty?

Helen Ifeagwu: Yes, of course. I think a lot of artists that we love often create their best work when they’re going through the worst periods of their lives, and every artist can relate to that because if you think about it this way, it’s a form of energy, and you’re transmuting that energy to create something new. If it’s very negative or destructive, you could take it and then put it out onto something. Unfortunately, that’s sometimes when the best art is made.

You see this in movies and even in music. I watched tonnes of documentaries of artists I like, and it’s like, Oh, I was struggling with addiction or this and that, but I made this album or piece. But we love the art piece that the artist has created as a result.

I think I can relate to that too, because I had a lot of dark periods myself. And that is when I was able to focus and make the best art because I was able to just completely look for an escape. I just become addicted to something that will help me focus less on things that destroy me in a way and then use that to make new art. Yeah, beauty masks pain, and we use art to beautify things as well.

FAB: And how do you balance aesthetics with honesty?

Helen Ifeagwu: I think I could be more honest in my work. I still lean a lot toward perfectionism and needing things to look nice and aesthetic. If I were more honest, maybe my work would be a little less polished, a little less “finished”. But I’m not in that stage yet.

FAB: Do you always understand your own work when you finish it, or do some pieces only reveal their meaning to you later?

Helen Ifeagwu: No, not all the time. There’s this one piece I’m currently struggling with a lot. I had a clear idea in my head at first, but I’ve been working on it for so long—it’s always just in the background, and the more I work on it, the more I’m like, wait, what was I even thinking? I’m not sure anymore. I think I have to wait for everything to come together—wait until it’s done—for it to make sense to me.

Sometimes I feel like my recent work, especially the ones rooted in symbolism, is like reading a book you don’t understand the first time. Then you finish it, and suddenly you’re like, Ohhh, chapter one! That makes sense now. So yeah, the more I explore symbolism, the more abstract the process becomes while creating, and then afterwards I’m like, Ah, okay, this actually all makes sense. I love reading. I love literature, reading a book and then discussing the themes.

I can’t even watch a single movie without researching afterward to figure out what every single little detail meant. That’s why my art is so layered—it’s because that whole meaning-finding process is so much fun for me. I really enjoy discovering meaning after the work is done.

The Language of Visual Art in Afrofuturism

FAB: Is there any book in particular that had a strong impact on you or your life?

Helen Ifeagwu: 1984 by George Orwell. It’s really good. I have many books I like, but for some reason, I was drawn to that one when I was like 11 or 12, not even through school, though we did read it in school later. It’s just so eerie and weird.

One of my favourite genres is retrofuturism. I also apply elements of Afrofuturism in my work, but retrofuturism inspires me in so many ways. It’s basically an art style from the 60s or maybe the 80s where people were trying to imagine the future through the lens of their current time. It’s kind of weird and doesn’t make much sense to us now in 2025. If you see photos or paintings from that genre, it’s like flying cars, old-school TVs with more channels—just small futuristic tweaks to things from that era.

So for me, it’s like looking into an alternate dimension. For instance, what could’ve been if 2025 wasn’t how it is today? That’s also the vibe of 1984. It’s very dystopian. It influences me a lot even in recent work. Like the painting I did called Dystopia, with a West African woman in a futuristic war against AI or something. That piece was definitely inspired by the book. And the book itself? It’s so uncomfortable to read, just uncomfortable. The movie is even worse.

FAB: What’s your relationship with interpretation, especially when audiences misunderstand or mislabel your work? Is silence ever your chosen response?

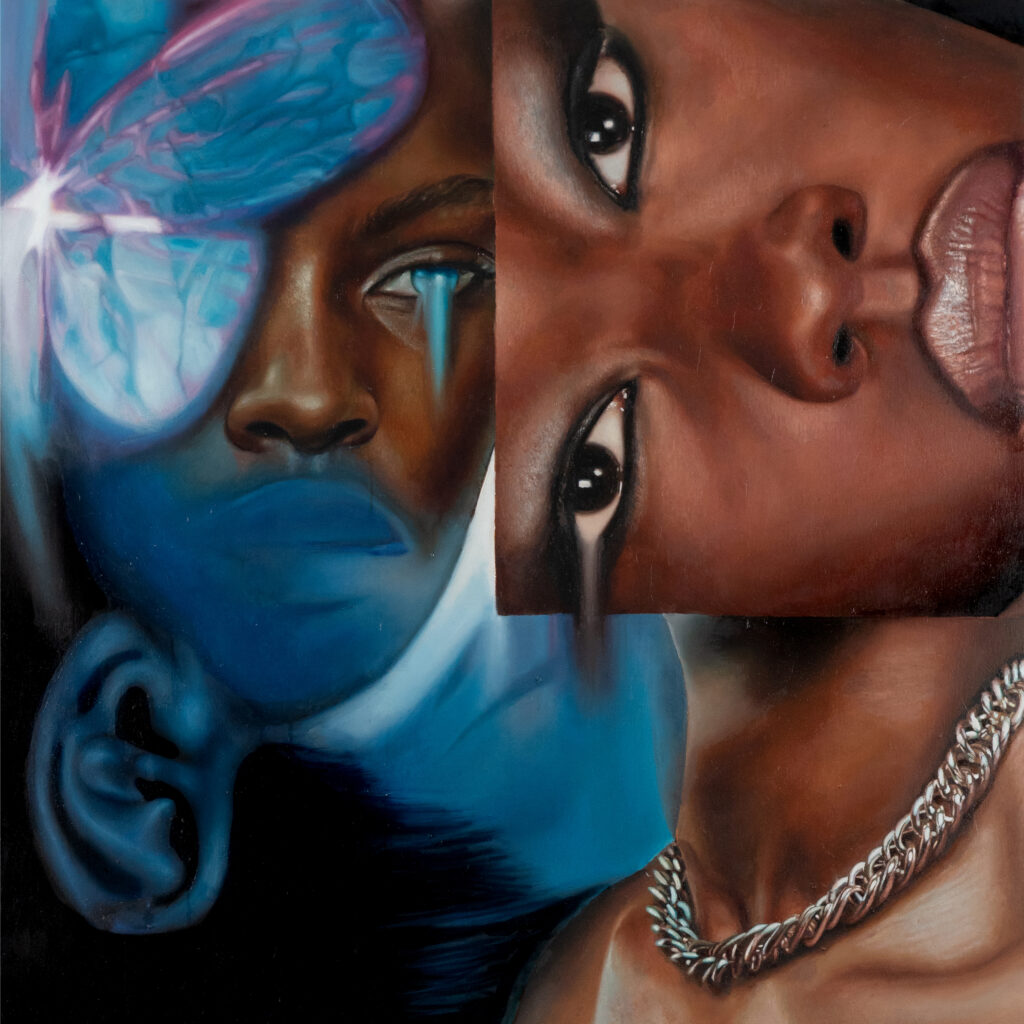

Helen Ifeagwu: No, I love interpretation. I love it, and I live for it. That’s why I enjoy doing exhibitions and talking to people at them. It’s honestly my favourite part. The best one I can think of is my painting, “Clones”, the one with the man holding these women like this. When I first exhibited it at my solo show, so many people had different interpretations of what they thought it meant. Some focused on the symbolism of him holding them, the way the women are shiny, almost like ice cream in a way.

For me, the way I explain it is that I draw a lot of influence from society, how I observe it and from Black culture, especially hip-hop culture. I often feel that women are viewed as symbols of worship but also as objects of pleasure. The ice cream reference is about being seen as delicate, fun, and desirable but not taken seriously.

The man’s hand has a pimp ring, which symbolizes hip-hop culture and wealth. The women are silver, representing luxury, something valuable but still objectified. Then there are also these heads in the background looking at each other, hinting at a hospital setting—people becoming indistinguishable, or ‘clones’, in a way. That’s why it’s called Clones.

But then, there was this older African woman at the exhibition. We were in a group talking about the painting, and she said, “Actually, I don’t agree with what you guys are saying. You women know.” We were like, What? And she said, “Yeah, for me, I like that the man is holding them like this. He’s protecting them. He’s probably wealthy—look at his jewellery. That’s important. I think we need men like this—men who protect us. We are their prize.”

And I was like, Wow, that’s true in its own way. I loved that she saw something completely different from us, and then it sparked a deeper conversation about relationships, culture, and society. I thought, Wow—this is what my painting did. We ended up talking about it for 30 minutes, and that was really cool.

FAB: Afrofuturism is often associated with music or fashion, but your work uses fine art as a medium. What do you think painting brings to this movement that other forms can’t?

Helen Ifeagwu: For me, my influences within Afrofuturism often come from the graphic and visual parts of the movement, the illustrations, comics, or even movies like Black Panther. I’d say I contribute to the visual side of Afrofuturism in that way. And yes, I do bring in fashion elements here and there—little touches of futuristic aesthetics.

I even had a painting I never finished that featured a dystopian background and a Black face that was half-robot. I didn’t complete it, but it was very much part of that visual storytelling. My work adds to the visual language of the movement, especially inspired by Afrofuturist books and comics.

Art as a Mirror and a Portal

FAB: You’ve described creating a parallel world in an Afrofuturist utopia. What does that world look like, and who is it for?

Helen Ifeagwu: Oh, I love this question. What does it look like? I think I’m still getting there. I’m still building it. Right now, I’m going through a phase where I feel like I’m painting really slowly. I don’t know what’s going on with me. I think life’s just been hectic—lots of events, being more social, more out there. But I really want to get into doing large-scale paintings where I can fully explore that retrofuturism idea—imagining myself looking into a different dimension. It’s about imagining how things could be or how they might have been—just not how they are right now.

As for who it’s for? I don’t know. Sometimes you create art just so it can exist in the world and inspire whoever it needs to. Sometimes it’s not even for you anymore. The creation process is personal—it heals you, spiritually and emotionally. But the moment you release it, it becomes for everyone else. Does that make sense?

FAB: How do you believe Afrofuturism can help redefine African identity not as a response to colonial history but as a proactive, imaginative force?

Helen Ifeagwu: In so many ways. Afrofuturism is really empowering. That’s what I love about it. It’s a celebration of who we are—our culture, our roots—and then mixing that with futuristic elements. I just think that’s such a powerful way to create. And also, it’s fun. It’s fun to live in a world of fantasy like that, and who knows? Maybe it’s not even fantasy. I think it gives us courage. It inspires us. It builds confidence not just for us now but for future generations. It doesn’t always have to be about reacting to slavery or colonialism or the past. It can be a new way of thinking—of moving forward in a powerful way.