Uganda’s fashion scene is bursting with untold stories, and Rebecca Hillone is bringing them to light. She went from being body shamed in school to winning crowns and designing for royalty. Her journey proves what happens when creativity finds its voice. As the founder of Rebecca Hillone House and The Kids Sewing Club Uganda, she confronts colonial mindsets that still drive African fashion. She doesn’t just make clothes, she redefines how we view talent, pageantry, and education.

But the journey isn’t all glam and gowns. Behind the sparkle, Rebecca exposes harsh truths: exploitation in the industry, government neglect, and the toxic beauty standards rooted in the pageant world. In this exclusive interview, Rebecca holds nothing back. She names names, breaks myths, and raises uncomfortable questions every African fashion stakeholder should answer.

From Body Shamed to Couture Queen: The Rebecca Hillone Story

FAB: Let’s begin with a powerful turning point, when you transformed body shaming into the launchpad for your fashion journey. It’s 2025, and we’ve just wrapped up the first quarter. Do you think the fashion industry is still too exclusive?

Rebecca Hillone: There are a few ways to look at it. Traditionally, high-end designer brands were exclusive because of their steep prices, limited availability, and targeted marketing. But I think things are starting to shift. More brands are making an effort to be inclusive and reach broader audiences. Even runway shows, which used to be invite-only for industry insiders, celebrities, or a handful of influencers, are becoming more accessible.

FAB: You’ve mentioned how pricing and runway access both contribute to exclusivity. You also launched your brand in response to what you saw happening in the industry. What are you doing differently to challenge those standards?

Rebecca Hillone: From my experience, yes, fashion is still exclusive. Just looking at my clientele tells you that. I mainly dress queens, Miss Uganda, Miss Tourism, and others. But when I started, I had no formal education in fashion. I was just a passionate creative, and I realized that creativity doesn’t need permission. That realization showed me I was in the right place to express myself. And with time, I connected with the right people, the queens, the pageant masters.

Of course, growth changes things. As I evolved, I began designing couture pieces and high-end garments. But I never forgot the importance of accessibility. That’s what drives my work now, creating pieces that are still luxurious but open to more people.

Rebecca Hillone on Pageants, Privilege, and Pushing Through

FAB: You’re the official designer for Little Mister and Miss Africa 2025. Do you think pageantry reinforces unrealistic beauty standards, or do you see it as a platform for empowerment?

Rebecca Hillone: Honestly, it’s both. On a personal level, I’ve competed in pageants, so I understand the experience from the inside. Whether you win or not, it’s what you take from the experience that counts. For me, pageants opened doors. I gained exposure that brought in the clients I work with today. Without that platform, I might not be where I am.

But yes, there’s a flip side. Many pageants still uphold very rigid and exclusionary standards. That’s why we’re seeing a rise in alternative pageants with specific themes. In Uganda alone, there are over 50 pageants, some for cancer survivors, some for the visually impaired, and others with more inclusive values. It’s important for people to choose the platforms that celebrate them for who they are.

That said, even in these progressive pageants, there are still high, often unrealistic, expectations. In some of the bigger ones, success can depend on how much money you invest. You might literally have to buy the crown. So again, it comes down to the individual. With or without the title, you have to recognize your own growth and value the exposure you’ve gained.

As for me, I’m evolving with the industry. I’m now designing more inclusive gowns, pieces that work for everyone, from brides to wedding guests. The pageant world gave me a foundation, but I’m building beyond it. I’m a living example of how pageants can empower. But I also see the need for change, and I’m working to be part of that shift.

What the Kids Sewing Club Uganda Is Really About

FAB: Tell us more about the Kids Sewing Club Uganda. I think it’s an incredible initiative.

Rebecca Hillone: I remember being in Primary Two when I started telling my mom I wanted to be a model. I’d sketch dresses all the time. But growing up, I didn’t get much support, mainly because of the traditional African mindset around education. In our society, there’s this idea that only careers like medicine, engineering, or aviation are worth pursuing. If you’re not a doctor or pilot, you’re seen as insignificant.

But over time, I realized something powerful: talent can take you just as far, sometimes even further. Talent allows people to express themselves and build lives around what they love. That realization made me think, if I didn’t get the support I needed back then, why not create that opportunity for the younger ones?

Most of my work has been with children, Little Miss Uganda, Little Miss Tourism, kids’ and teens’ pageants. I’ve dressed more kids than adults. And I’ve seen their passion. Give a child the chance to explain a dress made just for them, and they’ll do it in seconds. Yet, that same child might spend a whole term struggling to understand a math equation. Kids take a whole term or year to learn certain things at school, but in just days, a kid could explain a complex outfit design without hesitation. That said a lot to me.

So, I launched the Kids Sewing Club Uganda, not just as a holiday activity, but as a proper club focused on fashion and design for children aged 4 to 12. As far as I know, there’s nothing like it in Uganda. Some fashion schools have short programs, but this is a dedicated space just for kids.

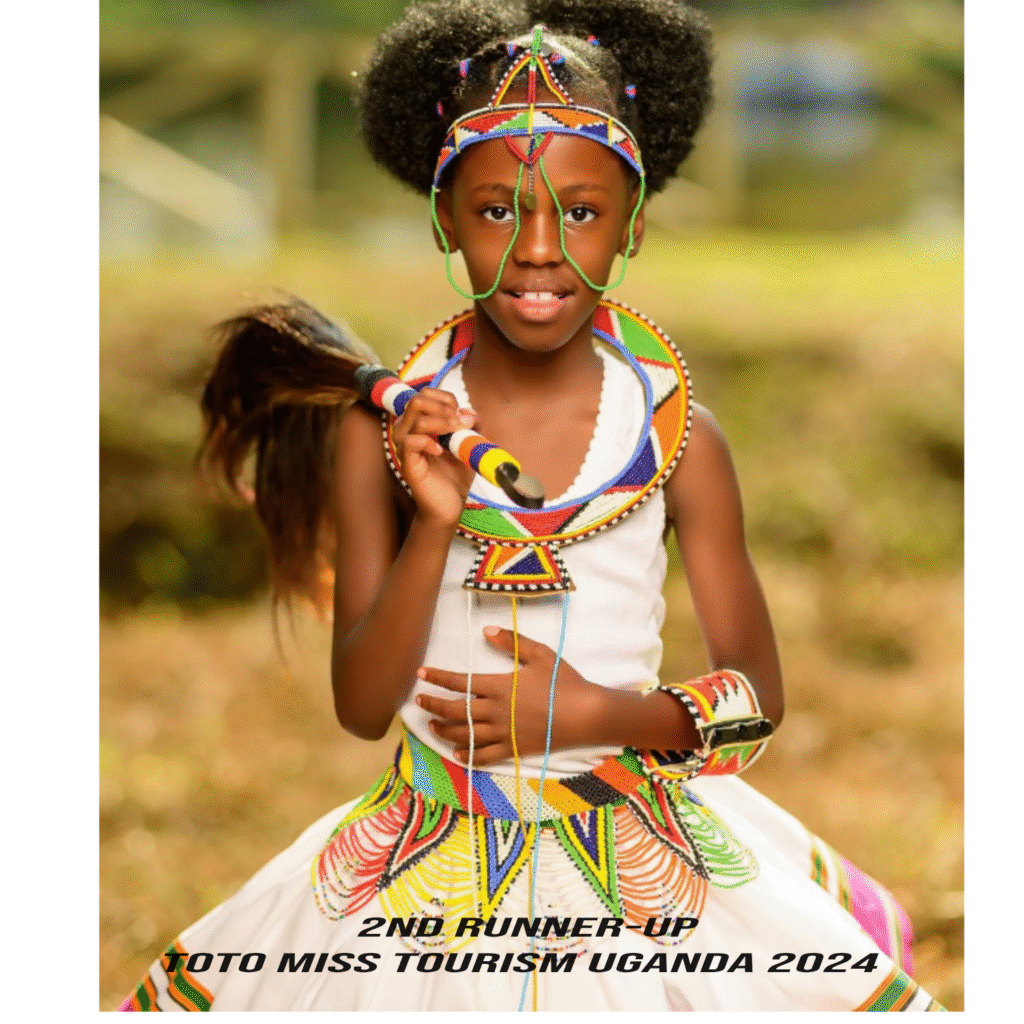

So far, we’ve registered six children. We deliberately kept the number small to ensure we offer quality training. The feedback has been amazing—parents are excited, and we’re proud to have Little Miss Tourism Uganda and the Uganda Tailors Association as our official partners.

FAB: Six kids already? That’s amazing. What’s been your most hilarious or chaotic moment with them? Because kids can be a handful!

Rebecca Hillone: Oh, definitely! Their attention span is no more than two hours, but within those two hours, they absorb things that some university students take weeks to grasp. I’ve been blown away watching how they express themselves while making outfits.

And here’s the beautiful part: nurturing a child’s talent early on gives them confidence and direction. They grow up knowing who they are, focused on making the world a better place—not burdened by outdated systems. These kids are not only inspiring other children; they’re influencing their parents too. They’re helping families break out of those limiting beliefs that colonial systems left behind.

Now, my funniest moment? It happened during modeling training. I wanted a girl to walk a certain way, and she just looked at me and said, “No, I’ll do it my way.” So, I let her. She got on stage and… it didn’t go as she hoped. She came back and said, “Auntie Becky, now I understand. Teach me. What should I do?” I laughed and said, “You see?” It was chaotic at the time, but it taught her humility and the value of learning. She wanted to shine, but she needed to be willing to put in the work.

FAB: You’ve mentioned colonial mindsets. With so many international recognitions under your belt, have you ever felt underestimated because you are African?

Rebecca Hillone: Surprisingly, the doubt hasn’t come from white people. It’s been from fellow Africans, people who are still mentally colonized. Because I’m young, clients often look at me and say, “Wait, you’re going to design my outfit? No, I need a real designer!” But once they see the final result, they’re shocked. They say, “Wait, you made this? You’re serious!” And that reaction never gets old.

The more parents I work with, the more they begin to see beyond age or brand popularity. One parent came to me after a well-known designer had completely ruined her outfit. She was skeptical at first but said, “I’ve heard good things. Can you fix this?” I told her gently, “I don’t fix what I didn’t create. But we can start fresh and make something beautiful together.” That trust means everything to me.

Another thing I’ve noticed is how clients bring AI-generated designs now. They show me a computer-generated image and say, “Becky, I want this.” I tell them, “Sure, I can replicate it, but that’s not my design. That’s someone else’s vision.”

And here’s the truth: out of ten clients who’ve brought AI designs, none of them won their pageants. But the ones who sat with me, brainstormed, and co-created something original – those clients won. The others ended up in competitions where several contestants were wearing the same AI-inspired pieces. It cost them the crown. People forget that everyone now has access to the same tech. But originality still wins. Always.

Who’s Holding Ugandan Fashion Back?

FAB: Uganda’s fashion industry is clearly evolving. But do you think the country is doing enough to support homegrown talent?

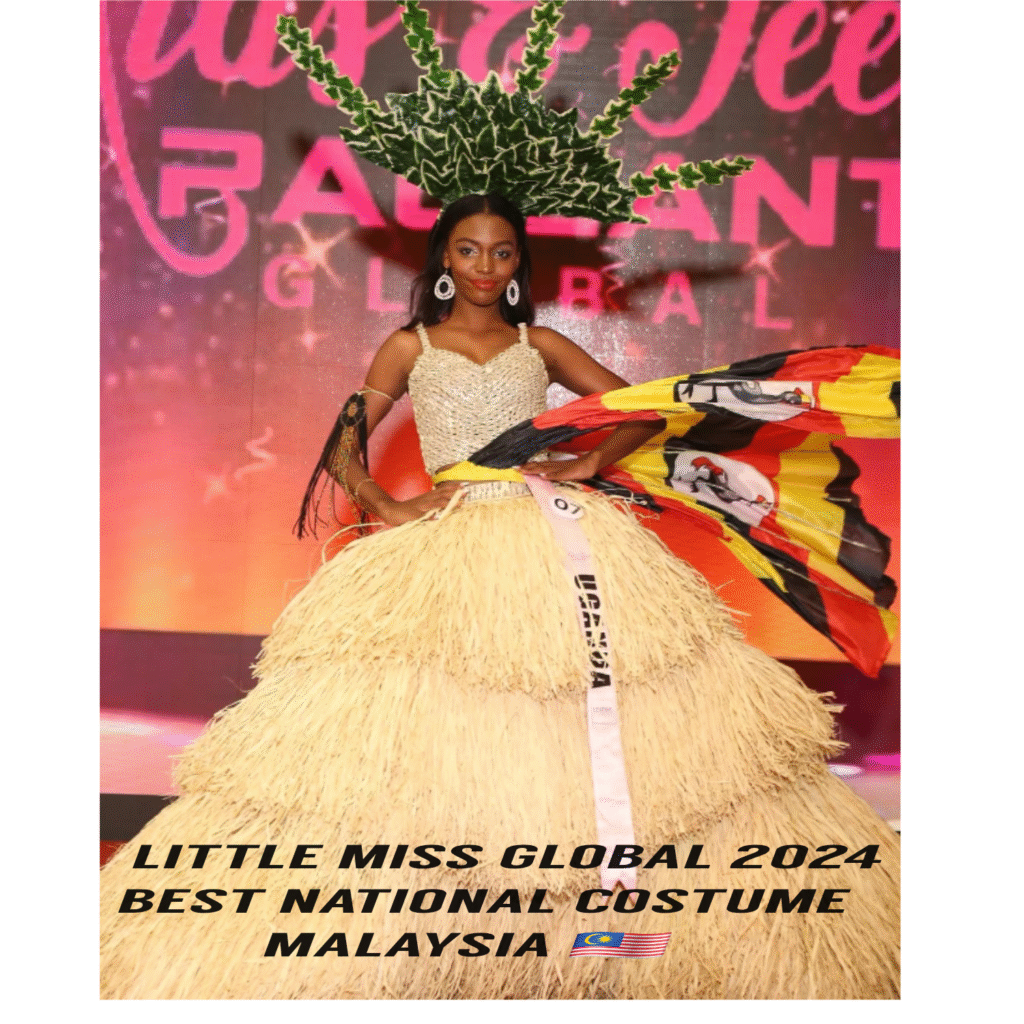

Rebecca Hillone: Not at all. Honestly, I’m not even sure if there’s an effort being made. When our queens travel abroad to represent Uganda, whether in Malaysia, Dubai, or Egypt, there’s this widespread assumption that the government will step in with support. But that rarely happens.

And it’s not just about the queens. Let’s talk about the tailors. I once attended a meeting with the Uganda Tailors Association, and one of the designers raised this exact issue, urging the government to take real action. When you look at Nigeria, for example, it’s clear they have better support. I genuinely believe Nigeria is the fashion capital of Africa. Sometimes when I see what Nigerian designers are doing, I think to myself, “Are these people even on the same planet as us?”

So yes, I don’t feel supported at all by the Ugandan government. They form associations and talk about initiatives, but the actual support—if it exists—is unclear. It’s blurry and inaccessible. It feels like it’s floating somewhere in the clouds, never reaching us.

Take my Kids Sewing Club as an example. It was a strong initiative, and I reached out to several government officials, including the Minister for Children’s Affairs. I also contacted others who are known to support children, but I got no response. Later, I discovered that some of these individuals were diverting allocated funds for unrelated purposes. Of course, they don’t say this outright. Instead, they hide behind “charity programs.” But the money is meant to buy something life-changing, like a sewing machine. Charity has become a convenient cover, a smokescreen. So really, it’s up to us. I don’t know if this message has reached the right people, but until the government steps up, we’ll keep pushing on our own.

FAB: Let’s shift focus a bit. What’s the biggest roadblock for Ugandan designers today?

Rebecca Hillone: It varies for different people, but for me, the biggest challenge is access to financing. You can’t be a fashion designer without a sewing machine, and that alone requires capital. So yes, funding is the major hurdle. Without it, nothing can begin. Access Support for African creatives.

Beyond financing, we lack proper marketing and branding. You’ll find designers who start with evening dresses, then shift to school uniforms, and later pivot to something else entirely. There’s often no clear niche. Even with funding, if you can’t brand or market yourself effectively, you’ll struggle. And many designers are struggling with that.

There are also other issues, like taxes. Materials brought into Uganda are heavily taxed, and this came up during a discussion with the Uganda Tailors Association. These high taxes affect everyone trying to import fabrics or tools. It’s excessive.

Then there’s the lack of protection for creative work. In countries like the U.S., if Louis Vuitton releases a new design, it’s protected; you can’t just copy it. But here, you can launch a design today, and by tomorrow, someone’s already duplicating it. There’s no reliable system for intellectual property protection, so people steal patterns and brand names with ease.

Some of the blame also falls on us. A lot of creatives don’t invest time in upskilling or mastering their craft. Instead, many complain that tailors ruin clothes or fail to meet expectations, but they haven’t truly developed their skills or carved out their niche. That’s another major issue.

FAB: You’ve mentioned upskilling a couple of times, especially around branding and marketing. You’ve also partnered with institutions like the Uganda Tailors Association and Baroma Vocational Institute. Would you say fashion education in Africa is keeping pace with global industry trends?

Rebecca Hillone: That’s a tough one. One thing that surprises me is how you can admire a designer’s work, reach out to them, and then discover they don’t actually know much. What’s worse is that it’s often these same people—those lacking deeper knowledge—who are the most eager to teach. In one sense, it’s admirable. But it also leads to a cycle where underqualified people train the next generation of underqualified tailors.

When it comes to fashion institutions, many students give up soon after graduating because what they learned doesn’t help them in the real world.

Another issue is how fashion education is treated culturally. In Uganda, and perhaps in other parts of Africa too, when a child struggles academically, parents often push them into vocational training. So you’ll find a talented dancer forced into fashion design, wasting years studying something they have no passion for, only to return home feeling stuck.

Also, most institutions don’t challenge their students. A few are starting to do better, but the majority just want to make money. As long as a student can cut a basic skirt, dress, or pair of pants, that’s considered enough. But real design is more than that. It’s about originality and innovation. I remember a designer once told me, “Be the kind of designer who sees a trend and doesn’t just copy it—improve on it. Compete with it.” That mindset really stuck with me.

The unfortunate reality is that many fashion graduates come out of school with very little practical skill or creative confidence. Some private institutions are trying to change this by introducing creativity-focused curricula, but even then, they’re not investing enough energy or resources.

I recently spoke to members of the UVTAB board—the body responsible for certifying vocational students at different levels. They’re planning to introduce a course dedicated to creativity, which is promising. The aim is to encourage students to think differently because every item in fashion began as someone’s original idea.

Still, fashion education in Uganda has a long way to go. Many schools prioritize profit over quality, and they end up producing designers who damage the industry’s reputation. That’s why people still say, “Tailors are destroyers.” So yes, there’s a lot of work to be done.

FAB: If you could redesign one iconic historical Ugandan outfit with a modern twist, especially considering the competitive products you’ve seen out there, which would you choose and why?

Rebecca Hillone: Oh wow, that’s a good one. As a designer, I work with traditional fabrics and love incorporating materials that were used in the past, like bark cloth. I don’t have one specific outfit I’ve always wanted to change, but if I had to choose, I’d go with what we used to call the busuuti, which has now evolved into what people know as the gomesi. I’m not really a fan of the full look of the gomesi, but the busuuti in its earlier form was really beautiful. I’d love to reimagine that.

FAB: You’ve designed for everyone from kids to beauty queens. On a lighter note, who’s the hardest to design for?

Rebecca Hillone: That’s an interesting one! Between the little queens and the big queens, I’ve found the older ones more challenging. Here’s why: they’re usually funding themselves, and while they want to wear the best, the best comes at a cost. So, I often have to compromise on the creativity of the design because of their budget constraints. That limits how much I can truly express myself.

In those moments, it feels like I’m not creating from joy, but out of necessity—and that can be disheartening. Designing for them also requires a lot more time and thought because I often use unconventional materials to create something unique, wearable, competitive, and portable. But again, the budget doesn’t always align with that vision.

Another challenge is communication. Some of these queens live far away, and while distance isn’t really the problem, miscommunication is. I always explain how to wear and present the outfit—for instance, “drop this first,” “pull up the wings,” “then do that”—but when they get to the stage, they do it all wrong. I suspect it’s often a language barrier or just nerves.

They also tend to stress and cry a lot! They’ll say, “Becky, please, make this for me; I’ll pay you later.” Meanwhile, when it comes to children, their parents go all out. They’ll do anything to ensure their kids win. And honestly? Most of the kids I’ve dressed have won. Every time.

African Fashion Education: Broken or Just Misguided?

FAB: Beyond using eco-friendly materials, what radical steps do you think African designers should take to redefine ethical fashion, especially now that it’s 2025?

Rebecca Hillone: First, we need to address fair labour practices. Designers should ensure that everyone involved in the production process, from textile makers to tailors, is paid fairly. I once applied for a job where the workload far outweighed the pay, and it made me understand why many people are leaving the field. It’s not sustainable.

Secondly, designers must be culturally respectful. It’s important to preserve traditional African patterns, fabrics, and aesthetics, but we must do so with a proper understanding and sensitivity to their origins. We also have to be more accountable. If a client isn’t satisfied with an outfit, the designer should take responsibility. Many don’t, and that’s a problem.

Another thing: we need to design for everyone. That includes people of all body types, all ages, and all abilities. African designers should understand that our people come in all shapes and sizes. For instance, I’ve struggled with making something for someone whose body shape doesn’t fit the mold that many designers are used to. We must be more inclusive.

In advertising too, there’s a lack of diversity. In Africa, I rarely see plus-size models represented. We still tend to stick to a specific look: tall, long legs. Maybe it’s because they think it makes the outfit look better? I’m not sure.

Also, the fashion industry generates so much waste. People keep buying and discarding clothes. But I’ve seen some promising developments, like designers recycling fabrics and initiatives such as the Kids Sewing Club, which empowers communities by engaging with specific groups. We need more of that.

FAB: If you had to describe your brand’s aesthetic in one song, what would it be?

Rebecca Hillone: Afro-centric elegance. That’s the best way I can put it. It’s rooted in African identity, but there’s a refined elegance to it through the fabrics, the silhouettes, and the craftsmanship. It’s African, but in a very creative and polished way.