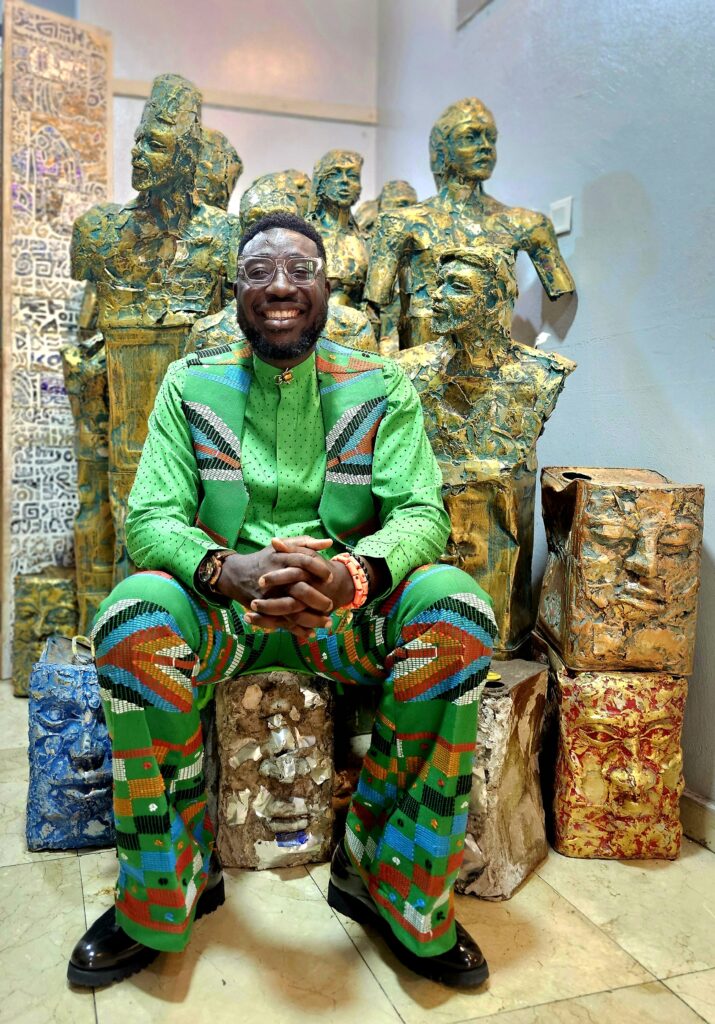

Welcome back to Part 2 of our interview with Gerald Chukwuma, where we continue to unravel the creative genius behind his artistry. In this section, Gerald Chukwuma opens up about his approach to overcoming challenges, the importance of self-reinvention, and how his work connects with various industries like fashion and furniture design. He also discusses the essential role that creativity plays in not just art, but in business, culture, and beyond.

FAB: There’s a growing understanding among creatives now that even if they lack administrative skills, they can hire someone to manage that side of things.

Gerald: Agreed.

While management is crucial, it’s better to learn and grow through management than to fail without it.

FAB: Now, let’s talk about the issue of hiring managers. There’s this common problem in the industry, like how music artist Portable puts it, of management ‘ripping you off.’ For example, an artist could sign a deal worth 100%, but management takes 70–80% of it. And then, fans look at the artist’s presence everywhere—on TV, radio, events and think, “You should be making a lot of money!” But the artist is struggling and saying, “I’m starving, man, I’m really, really hungry.”

Gerald: I know that feeling all too well. It’s happened to me more times than I can count. Without naming names, I’ve experienced it repeatedly. The reality is this: while management is crucial, it’s better to learn and grow through management than to fail without it.

I’ve seen artists crash and burn because they believed they should be somewhere they’re not, and that can be devastating. Many talented artists I know disappeared because of that disappointment. That’s why financial literacy should have been introduced as early as secondary school. My experience as a first-class graduate from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, gave me perspective on this. One of my lecturers once asked me, ‘Gerald Chukwuma, why are you in Lagos? Come and lecture here!’ I was willing, but under one condition: I told him, “I’ll lecture, but I don’t want to be paid for it.”

FAB: Why not?

Gerald: Because if I’m paid, I’ll have to follow the institution’s curriculum, and often, that curriculum doesn’t reflect the realities outside. If I teach for free, I can use their curriculum but tell my students the whole truth. If they don’t like it, they can fire me, and I’ll walk away.

In fact, one of the vice chancellors offered to sponsor my master’s degree. He came to my studio in Yaba, impressed with my work, and made the offer. But I told him, ‘If I lecture, I want to do more than teach theory. I want us to create practical results, like setting up a factory within the art department. Let’s convert creativity into something tangible. Not every student wants to be a visual artist; some want to make shoes, furniture, or other products. We can bridge the gap between art and industry by offering them the tools and technical skills they need.’

Imagine producing beds designed by art students from the University of Nigeria and selling them globally as artist-made pieces. That would make a real difference.

FAB: That’s an incredible approach. So, back to management—what’s the key?

Gerald: Management is essential for every successful artist. It’s not the other way around. Many artists succeed because their management helps them navigate the business side. For example, I was invited to a major event recently, and I didn’t attend, not because I didn’t want to, but because, as an artist, I didn’t see the importance. A good manager would have insisted I go. They would understand the significance of ‘showing face’ at such events, which is something I’m still learning. Contemporary artists today, especially the Gen Z crowd, understand this better. They’ve grown up in a different environment, more tech-savvy and business-oriented. Millennials, like me, are playing catch-up.

And it’s not just about learning the business—it’s about adapting to the culture that shaped us. I have children, and even though they’re pursuing arts, they’ll have to be computer-aided artists. Technology is a part of everything now. It’s the same with management; it has to be part of the process, not a parasitic force. It should be a give-and-take relationship.

FAB: You’re right. That balance is crucial.

Gerald: Exactly. I’ve worked with a gallery in the UK, and the experience has been amazing. We don’t even have a formal contract. When the gallery sees an opportunity for me, they suggest ideas that could benefit my career. There’s no exploitation, just a collaborative approach. Unfortunately, I’ve made many mistakes in my career due to the lack of proper management, but I’ve learned from them.

FAB: You want to talk about one?

Gerald: Yeah, I’ll tell you one. There was a time when I was very ill—extremely ill. I had been to several hospitals, undergone numerous checkups, but no one could pinpoint what was wrong. During this period, I couldn’t work for a long time, and the bills kept piling up. I was in a bad state.

In fact, I remember visiting a gallery, and the gallery owner, seeing how unwell I was, wired me half a million naira. He saw me in the car—my wife had driven me—and I think he didn’t believe I would make it. That time was tough.

Once I started recovering and returned to my work, I had nothing to fall back on except the pieces I had already created. There are many instances like this, but I’ll share just one. I sold a few pieces as I could manage, with the first buyer essentially giving me a lifeline because I had to survive. One thing that has always kept me going is that my art serves as my therapy. Even when I was so unwell, I would walk into my studio, pushing through the pain, just to keep myself grounded, knowing that there was still a future ahead.

One of those works later ended up in an auction, and it was sold at such a ridiculous price that the gallery representing me called me, and I was embarrassed. I had sold it out of desperation. Artists face this dilemma often—no artist escapes it. Your rent is due, and you can’t afford to pay it. It’s your studio rent, and if you’re a true artist, you will even sell the clothes off your back to keep your studio. The studio is sacred; losing it would be devastating.

Then, someone walks in, already knowing your financial situation. They offer to buy your work, but not for what it’s worth. You quote the actual price, and they say something like, “I know that’s the real price, but because I love the work, I’ll give you half since we’re friends.” It’s not uncommon. They know the value of your work but exploit your need. And because you’re desperate, you accept.

It’s one of the unfortunate mistakes many artists make, but we don’t have much choice sometimes. There was a woman I visited who had several pieces by a renowned artist—works that are worth a fortune. She told me how she acquired them, and I couldn’t believe it. You can have an attachment to someone and end up giving them your work at a fraction of its value.

Later, you’ll see that same work in places you never expected, and it’s selling for far below your intended price. It hurts, but despite all of this, I’ve never regretted any of those sales, and I never will. People ask, “Why did you sell it so cheap? Why did you make that decision?” I just laugh and say, “That’s my journey.”

It would only matter if I stopped progressing, but I always tell them, “Wait for me a year, and you’ll see something new.” I can’t stop—it’s my life. Nothing can stop me, except the One who gave me this gift, and I know no one on earth has the power to stop what’s in me. Only if you’re not a true artist would you fear losing your best work. It’s a joke to think your best work is behind you. Sure, some pieces might be visually better, but they may not be your deepest work.

As an artist, fulfillment comes from sharing your story with the world. While some of these sales are painful, they are all part of the journey. I don’t regret any mistake I’ve made with my art because I’m still moving forward. Those mistakes were divinely orchestrated to teach me valuable lessons.

A butterfly doesn’t look back at its time as a caterpillar and think, “Oh, what a terrible phase, I was so ugly.” No, the process requires failure. There is no success without failure. It’s like an equation: failure + failure + failure = success. Take away the failures, and success doesn’t exist. We recognize light because there is darkness. Without darkness, how would we know light?

Take my trips for exhibitions, for example. For many of them, I cover 90% of the expenses out of my own pocket. People don’t know that.

FAB: Everyone would assume you’re sponsored.

Gerald: Yeah, but I pay for 90% of my expenses. Most of the time, the galleries cover the cost of moving the artworks, which is quite expensive. But I handle everything else—flying there, staying in hotels, eating, and buying materials for my art. I don’t see it as a burden, though. It’s all part of the process. It’s a journey. As long as you know where you’re headed and you’re confident you’ll get there, the challenges along the way don’t really matter.

FAB: I had so many questions prepared for you, but this is the point I say I prepared a different message but gave a completely different sermon…

Gerald: I just want to be straightforward because that’s the truth. The truth is bitter. When you have a script, you can’t always tell the truth. You try to be proper, to appear polished, and avoid coming across as a mess. But, no, no, no—that’s not reality.

It’s not an easy path, and let me shock you: just a month ago, before I met Harriet, I sat down and asked myself, Should I stop doing art? Yes, I seriously considered it. I asked myself, Aren’t you tired? The real question is, When will you be tired? What people see on the surface is often far from the reality.

Many artists are misunderstood. A lot of them are under immense pressure. That’s why people like Michael Jackson break down—they feel they must maintain an image, a front. When you build that front, you’re forced to keep it up. But if you don’t put on a facade, maybe as an executive or in some other field, no one notices when you’re struggling. You can take a break, recharge, and come back. As a creative artist, though, it’s different. You’re always under pressure to be relevant.

I watched a skit by Frank Ndehu recently. Someone asked him who he was, and when he replied, the person said, You’re not relevant anymore. And I thought, That’s exactly what happens to every artist. We constantly question ourselves: Do I need to be relevant? Why should I?

The standard of success for an artist is to remain successful forever.

FAB: You’ve spoken about the challenges of being in the limelight. There’s also a kind of pressure that artists face—one that you can’t always share with people.

Gerald: Just last month, I had a fantastic show in Austria. It was my first time there. I was cruising on boats, flying around, staying in hotels—it all seemed perfect. But at one point, I sat in my hotel room and thought, “Aren’t you tired?” And I was. The exhaustion wasn’t physical, it was from external pressures. It’s not an internal demon, it comes from the audience. They expect you to be a champion every day of your life.

The standard of success for an artist is to remain successful forever. But what happens when that success fades? If my artwork no longer sells for 40K, or my movie premieres aren’t full anymore, people lose interest. The pressure is immense. I’m not saying pressure is bad, but how do we manage it? When a gallery or film director sees that you’re no longer the “it” artist, they discard you for the next big thing.

If you don’t know how to manage yourself, you’re done for. It starts with losing yourself and can spiral into mental health issues—like Van Gogh. When I visited the Van Gogh Museum, I felt angry. They showcased his work from when he was in a psychiatric hospital, highlighting his mental health struggles. That’s the legacy left behind when an artist can’t handle the pressure.

But if you understand that there’s a divine purpose in your life and your work, you can push through. If I feel like I should become a farmer tomorrow, I’ll do it. I believe that God would lead me to be a creative farmer, not just any farmer. The creativity won’t stop; the pressure will.

Art, at its core, was meant to be functional. Even when we add beauty to it, the function remains. Take, for instance, a bamboo pot. Its primary purpose is to fetch water. Even if people don’t like the design, it still serves its function. That’s what I learned in Nsukka’s Department of Fine and Functional Arts, and it excited me.

The issue with actors and creatives is that they’re often celebrated for things other than their craft. An actor’s fulfillment should come from acting, not the hotel they own. Jeff Koons is a perfect example. Some people criticize him for creating plastic sculptures, but he sees the future. He doesn’t let frustration get to him.

We need to talk about this more openly, but often we avoid the conversation because we fear becoming “commercial.” There’s a misconception that commercial success diminishes an artist’s creativity. That’s false. The more resources you have, the more you can create. It only becomes problematic when money becomes your sole focus.

In art schools, they often tell you not to think about money. But if someone came to me and said, “I’ll give you 10 million Naira to pursue your master’s degree,” you’d bet I’d be fully committed to my studies, without the distraction of financial concerns.

There’s a sculptor I know, one of the best in the world, yet his works are undervalued. I bought several of his pieces, but nobody else would. Why? Because they reduced his work to “roadside art.” He was hungry, so he sold his art for peanuts. Some of us refused to accept that fate, but he didn’t know any better. People might say it’s his fault, but it’s more complicated than that.

Not all artists who struggle are lazy or incompetent. Just because I’ve had to sell my work for less doesn’t make me a “commercial roadside artist.” People don’t understand the sacrifices I make. If I tallied up the costs of traveling to exhibitions, they’d probably tell me not to bother. But then, I wouldn’t meet people like Harriet, and I wouldn’t have these opportunities.

There’s more to an artist’s life than their work. Brad Pitt’s legacy could be his hotel, not his movies. But society places so much pressure on artists, focusing only on their art, and it can be overwhelming.

FAB: You’re tempting me to dive into another topic — the diversification of portfolios for creative artists.

In the music industry, for example, we’re seeing artists diversify. Look at Rihanna with her Fenty brand, which is doing incredibly well. She’s still thriving musically too. I think there’s something dynamic about us as a continent. People often think that when an artist isn’t producing frequently, they’ve faded out. I love Meiyo Koi, and someone recently asked me, “Does he still sing? Is he still a musician?” I replied, “Yes, he’s doing well.” He doesn’t need to release an album every year; he’s likely involved in other ventures and still doing well. It’s like how we tend to stereotype. When an artist isn’t performing in the exact way we expect, we think their time is over, and we’ve moved on to the next big thing.

This brings me to another topic: the collaboration between artists in Nigeria. In the Western world, we’ve seen the rise of wearable art, especially in East Africa—Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda are leading this space. But when you think about Nigeria and Afropop, what imagery or style comes to mind?

Gerald: That’s an interesting question. What costumes come to mind?

FAB: Or what cultural elements come to mind when we think of Afropop?

Gerald: Unfortunately, culture seems lost in this context.

FAB: Why is there a gap in collaboration between artists in Nigeria? You’ve touched on this briefly, but is it because studying visual art confines one to creating only paintings or it doesn’t have to be? An artist could design furniture and thrive, right?

Gerald: Absolutely. It’s an institutional problem. If we could teach this idea within our institutions, things would change. Creativity is needed in every industry, not just art. If we could encourage creative minds to explore other sectors without feeling like they’re betraying their craft, we’d solve so many issues. Look at Mai Atafo, for instance. He’s known for his creativity, not just wedding designs. It’s the creative touch that makes his work stand out.

Take Eminem, for example. He became one of the greatest rappers not just because of his lyrical skills but also due to his creativity. His unique look—blonde hair and sharp eyes—caught Jay-Z’s attention. Jay-Z saw the creativity and realized he could break the norm. That’s creativity at work.

When I start an art institute, the first lesson would be that creativity isn’t confined to visual art. Wearable art, for example, is something we’ve always done. Art was initially both decorative and functional. Over time, it became more ideological and decorative because people wanted to control it—control the pricing, control the auction houses.

It’s essential for artists to branch out. If you can’t do it yourself, find someone who can help. Diversification allows you the freedom to create without worrying about financial survival. And guess what? It’s not just about money. If you’re a maker of doors, for instance, you’ll design better, more aesthetically pleasing doors. The same goes for any other industry—planes, cars, fashion—when artists are involved, the quality improves because they infuse creativity and beauty into their work.

Every industry needs creative minds, but they rarely give artists the credit they deserve. Industries hire artistically minded individuals to help shape their products and experiences, but they don’t always acknowledge the artist’s role. We need to move beyond just thinking about the studio as the only space for creativity.

Every industry needs creative minds

FAB: From what you said earlier, it sounds like you might be suggesting that, in some ways, you could be considered a consultant.

Gerald: Yes, exactly! You should be a consultant. Do you understand my point? You have so much knowledge, and it’s only natural to consult. You possess too much insight not to be in that role. But here’s the problem: people often expect consultancy from you for free because they don’t recognize its value. As a result, you start doubting whether it’s something you should monetize.

Catch the final part of this interview in Part 3, where Gerald Chukwuma shares his thoughts on the future of African art and his legacy. You won’t want to miss the conclusion!